The Lady of Bilton Possibly Gundreda: A Forgotten Heiress in Stone

- Guinevere Jackson

- 1 January 2026

- 0 Comment

The Lady of Bilton: A Forgotten Heiress in Stone

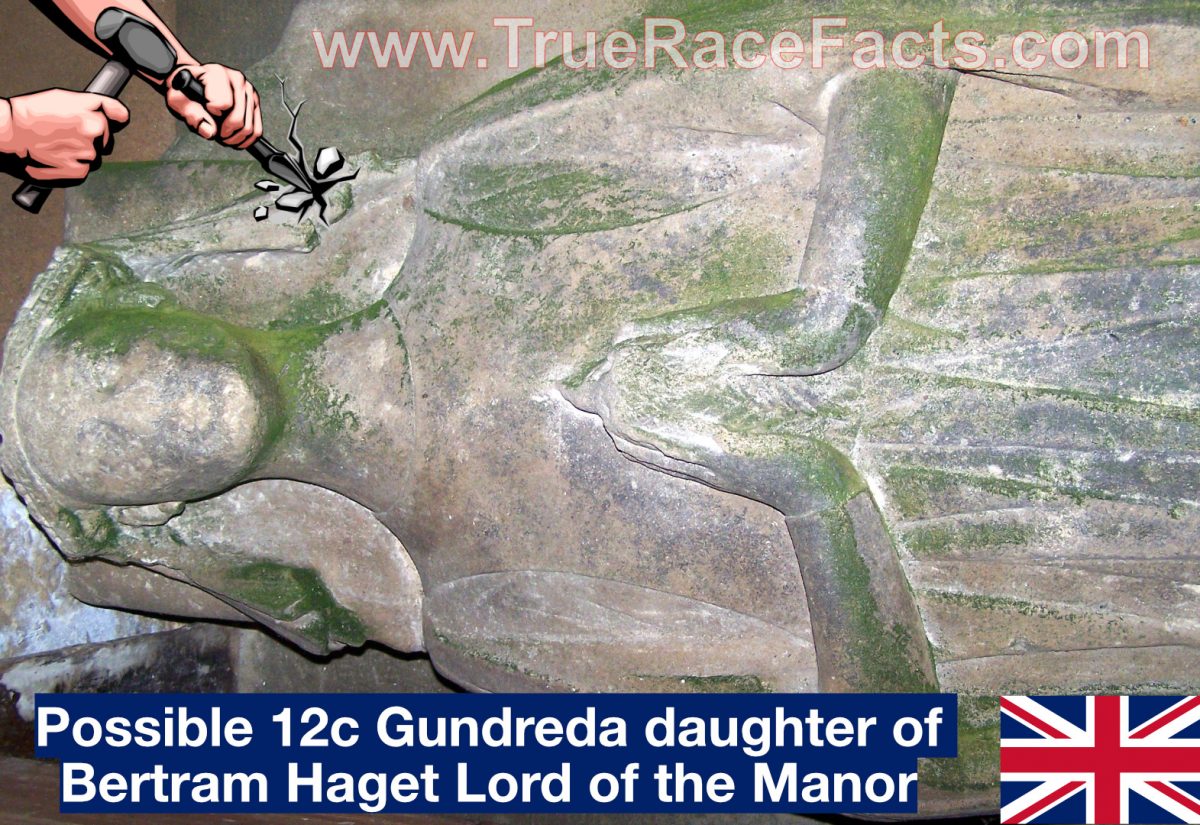

In the quiet village of Bilton‑in‑Ainsty, Yorkshire, the parish church of St Helen holds more than centuries of worship. Within its stone walls lies a medieval effigy of a young woman, a monument whose presence raises questions about noble identity, historical memory, and the selective editing of the past.

There is an old local tradition that this effigy represents Gundreda, daughter of Bertram Haget, Lord of the Manor in the mid‑12th century—a woman whose family established spiritual foundations in the landscape and whose name echoes faintly in charters and benefactions. While no contemporary inscription survives to confirm her identity on the monument itself, the archaeological and architectural context links the Hagets intimately to this place and its sacred sites. A Church Near You+1

A Priory Founded by Blood and Faith

Around 1160, Bertram Haget—identified in local records as the lord of the manor—donated land for a Cistercian priory of St Mary at Syningthwaite, a convent that endured until its dissolution in 1535. His daughter Gundreda is recorded as a supporter of the priory, giving money to endow the living of a vicar for St Helen’s Church in Bilton. Flickr+1

The church of St Helen itself was built in Norman stone around 1150–1160, likely by the Haget family, and remained closely linked with the priory at Syningthwaite. Wikipedia

Within this sacred space—linked by blood, piety, and landholding to a Cistercian foundation—lies an effigy of a lady of the manor, carved in medieval limestone and dressed in the attire befitting her class.

A Fragmented Face, an Unforgettable Outline

Time has not been kind to this sculpted figure. Unlike some medieval monuments that have weathered evenly, the face of this lady has been noticeably smoothed and sanded down, removing almost all surface detail. Lips have been greatly diminished or erased altogether. Yet, even in the absence of those carved features, the underlying outline and proportions remain clear to anyone who looks closely.

The nasal structure that remains is broad in form, and the faint contour of the mouth suggests full lips—features that survive beneath later alteration. This is not the random result of centuries of wear; its uneven pattern suggests selective smoothing, a deliberate minimisation of the very features that once may have identified her appearance.

Once, the effigy would have been more fully modelled and likely polychromed, making its depiction of a real person unmistakable. Today, even with the face altered, the geometry and remnants of form resist the attempt to erase identity. The stone still bears the trace of a swarthy, full‑featured woman—a truth that survives beyond the reach of chisel and time.

A Daughter of the Hagets: Status and Silence

If the effigy does represent Gundreda Haget, it would confirm what local history quietly preserves: that women of noble rank in Norman and early Plantagenet England were commemorated in stone, and that their memory was once sufficient to warrant a sculpted monument.

The Hagets were not an obscure family. Their benefactions—founding a priory, endowing a vicarage, and shaping local worship—placed them among the landholding elite of the Middle Ages. That a daughter of such a house should receive an effigy in the parish church is consistent with what we know of medieval patronage and commemoration.

Yet, what we see now is selective remembrance.

The figure remains.

Her posture is intact.

Her garments are legible.

But her face—her phenotype, the most intimate marker of personhood—has been deliberately softened. This pattern is not unique to Bilton. Across England’s churches, faces of medieval monuments have been smoothed or recarved as later generations sought to conform the past to newer aesthetic and racial expectations.

What the Stone Still Says

Despite the sanding and reduction of facial features, the effigy at St Helen’s Church still speaks:

It speaks of a woman of rank.

It speaks of a family influential in the religious life of the region.

It speaks of medieval identity rendered in stone.

And it speaks of the uneasy tension between what was commemorated and what later hands found inconvenient.

Even when surfaces are smoothed, the underlying structure resists erasure. The outline of this lady’s face remains a testament to an individual whose memory was once valued enough to be carved, and whose presence still lingers within these ancient walls.

Stone remembers what history tries to forget.

“They smoothed her face, but the stone still remembers the shape of her identity.”

Guinevere Jackson

Image citation Flickr, Getty and Wikipedi

Donate

Donate