1066c. William The Conquerer Black King of England

- Guinevere Jackson

- 8 August 2022

- 2 Comments

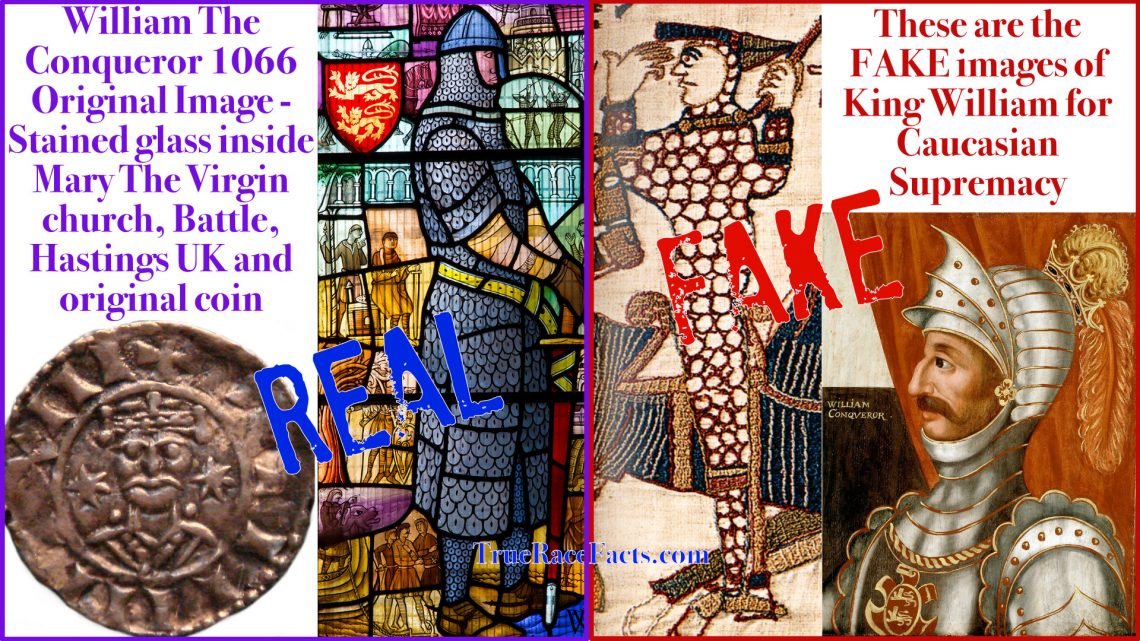

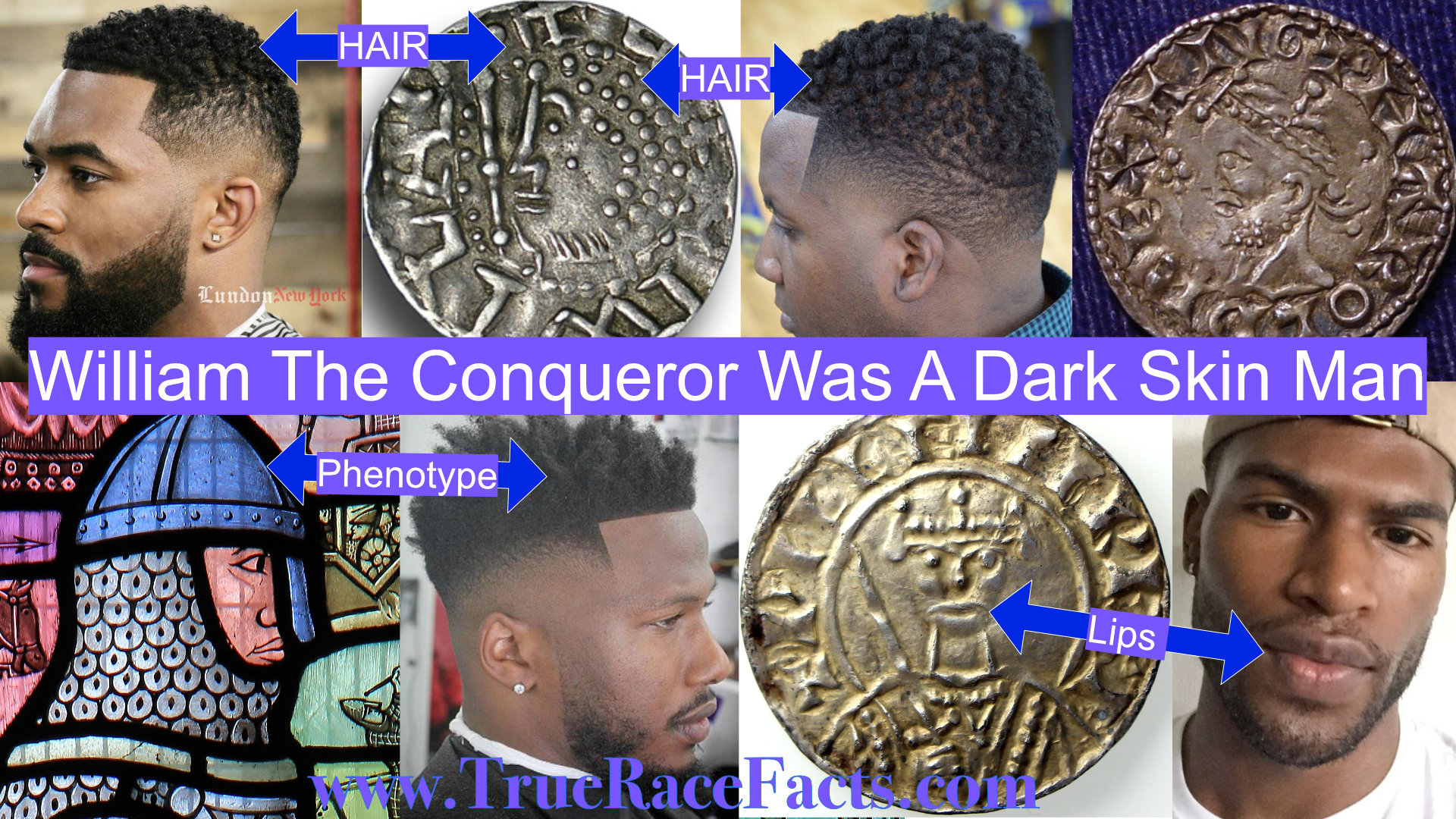

William I, also known as William the Conqueror, William, the Bastard or William of Normandy, French terms Guillaume le Conquérant or Guillaume le Bâtard or Guillaume de Normandie, (born c. 1028, Falaise, Normandy now France, died September 9, 1087, Normandy), duke of Normandy (as William II) from 1035 and King of England as William I from 1066, will go on record as the most outstanding King and ruler of the Middle Ages and beyond. He made himself the mightiest nobleman in France and then changed the course of England’s history by conquering the country. William the Conqueror’s image is inside St Mary The Virgin, Battle, Hastings, England. If anyone knew how King William looked, it would be Battle Hasting. The original coin with his large full lips would’ve been approved by King William.

William the Conqueror’s image is inside St Mary The Virgin, Battle, Hastings, England. If anyone knew how King William looked, it would be Battle Hasting. The original coin with his large full lips would’ve been approved by King William.

Not only was William I an outstanding leader, but he also changed the landscape of France and England with his fantastic architecture. Tourists travel miles to see his architecture that is still being lived in by the current monarchy of England and the Church of England. For a man with no formal education, he was indeed a wise man.

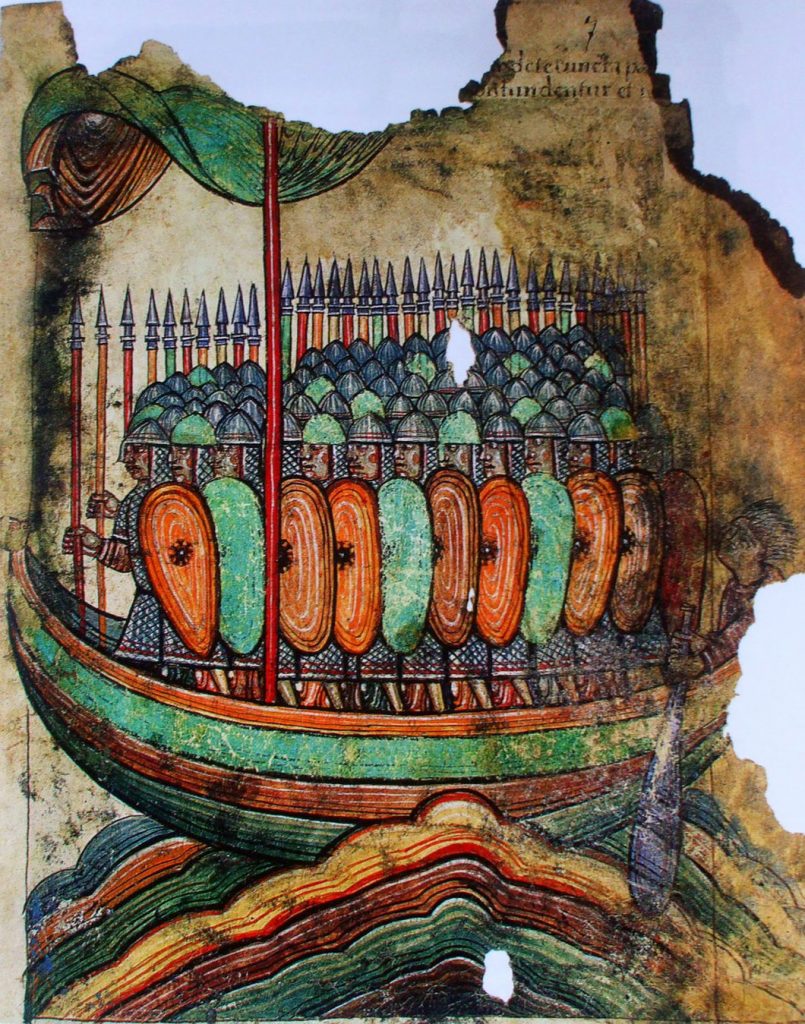

Norman soldiers crossing the English channel from La Vie de Saint Aubin d’Angers, an 11th-century manuscript

Early years

William was the eldest of the two children by King Robert I of Normandy and his concubine Herleva (also known as Arlette, the daughter of a commoner from Falaise, France). After William’s birth, Herleva married Herluin, viscount of Conteville, by whom she bore two sons and at least one daughter, including Odo, Earl of Kent (born c.103 died February 1097, Palermo, Italy), half brother of William the Conqueror and bishop of Bayeux, Normandy. In 1035 Robert died returning from a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, Israel. William, his only son, who he had nominated as his heir before his death, was accepted as duke by the Norman magnates and his overlord, King Henry I of France.

William and his comrades had to overcome tremendous obstacles, including King William’s illegitimacy which led to him being nicknamed William the Bastard. These difficulties likely contributed to William’s purpose and his dislike of lawlessness and misrule. His weaknesses led to a breakdown of authority throughout the duchy: private castles were erected, lesser nobles usurped public power, and remote warfare broke out due to disrespect. Willaim did not get the support he required because his enemies stood to gain by his death. His strong mother managed to protect him through the most challenging period of his life.

The Lion represents the House of Judah, descendants of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, Hebrew Israelites. Many European Kings, Noble men and Knights would go to Jerusalem, Israel yearly for pilgrimage; this means they knew they were Hebrew Israelites and never lost sight of it.

William learned how to control his youthful recklessness and learnt to calculate his risks on the battlefield. He was not a flamboyant commander like most before him. His methods were direct, and his plans simple. He ruthlessly exploited any opportunity available. If he was at a disadvantage, he knew to withdraw immediately. He never lost sight of his aim to recover lost ducal rights and revenues. Although he developed no theory of government or significant interest in administrative techniques, he was always prepared to improvise and experiment.

He had morals and was pious by the standards of the time, and he acquired an interest in the welfare of the Norman church. At just 16, he made his half-brother Odo bishop of Bayeux, combining the roles of the noblemen and high-ranking clergy in a way that did not greatly shock his contemporaries. Although Odo and the bishops that William appointed were not recognized for their spirituality, they soon strengthened the church in Normandy with their pious donations and administrative skill. William endowed several monasteries in his duchy, significantly increasing their number, and introduced the latest currents in reform to Norman monasticism. William presided over numerous church councils. He and his bishops passed important legislation against simony (selling church offices). He also welcomed foreign monks and scholars to Normandy, including the archbishop of Canterbury, England, Lanfranc of Pavia, a famous master of the liberal arts.

When Edward died childless on January 5, 1066, Harold was accepted as King by the English magnates, and William decided on war. He proceeded carefully, however, first taking steps to secure his duchy and to obtain international support for his venture. William consulted with his leading nobles, bestowed special authority on his wife, Matilda, and his son Robert, and appointed vital supporters to important positions in the ducal administration. He petitioned the pope in Rome and received the blessing of Alexander II, who was encouraged by Archdeacon Hildebrand (the future Pope Gregory VII) to support the invasion. He also appealed to volunteers to join his invasion army, winning numerous recruits outside Normandy.

Events outpaced William, however, as others moved more quickly. Tostig, Harold’s exiled brother, raided England in May but suffered defeat at the hands of one of Harold’s allies. In September, Tostig joined Harald III Hardraade, King of Norway, in an invasion of the Northumbrian coast. Although ultimately unsuccessful, Tostig and Harald’s attack had significant implications for the success of William’s invasion in the south.

The Rouen Cathedral seen from the Gros Horloge tower. The church was the tallest building in the world from 1876-1880, with a height of 151m.

The Battle of Hastings

By August, William had gathered his army and his fleet at the mouth of the Dives River. At this point, he probably intended to sail due north and invade England by way of the Isle of Wight and Southampton Water. But adverse winds held up his fleet, and in September, a westerly gale drove his ships up Channel. William regrouped his forces at Saint-Valéry on the Somme. He had suffered a costly delay, some naval losses, and a drop in the morale of his troops. The delay, however, yielded a significant benefit for William. On September 8, Harold was forced to release the peasant army he had summoned to defend the southern and eastern coastlines, leaving them without adequate protection. On September 27, the wind turned in William’s favour after cold and rainy weather. William embarked on his army and set sail for the southeastern coast of England. The trip was not without incident: William’s ship lost touch with the rest of the fleet, but he calmed his crew by supping as if he were at home, and contact with the other vessels was made not long after. The following morning, he landed, took Pevensey and Hastings’s unresisting towns, and began organizing a bridgehead with 4,000 to 7,000 cavalry and infantry.

Ruler Normandy, France

By 1042, when William reached his 15th year, was knighted, and began to play a personal part in the affairs of his duchy, the worst was over. But his attempts to recover rights lost during the anarchy and to bring disobedient vassals and servants to heel inevitably led to trouble. From 1046 until 1055, he dealt with baronial rebellions, led mainly by his kinsmen. Occasionally, Willaim was in great danger and had to rely on Henry of France for assistance, but during these years, William learned to fight and rule. A decisive moment came in 1047 when Henry and William defeated a coalition of Norman rebels at Val-ès-Dunes, southeast of Caen, a battle in which William first demonstrated his prowess as a warrior.

William’s army was in a narrow coastal strip, hemmed in by the great forest of Andred, and, although this corridor was easily defensible, it was not much of a base for the conquest of England. The battle season was almost past, and when William received news of his opponent, it was not reassuring. On September 25, Harold had defeated and slain Tostig and Harald at Stamford Bridge, near York, England, in a bloody battle with significant losses on both sides. He was retracing his steps to meet the new invaders at Hastings. On October 13, Harold emerged from the forest, but the hour was too late to push on to Hastings, and he took a defensive position instead. Early the next day, before Harold had prepared his exhausted troops for battle, William attacked. The English phalanx, however, held firm against William’s archers and cavalry. The failure to break the English lines caused disarray in the Norman army. As William’s cavalry fled in confusion, Harold’s soldiers abandoned their positions to pursue the enemy. William rallied the fleeing horsemen, however, and they turned and slaughtered the foot soldiers chasing them. On two subsequent occasions, William’s horsemen feigned retreat, fooling Harold’s soldiers, whom their opponents killed. Harold’s brothers were also killed early in the battle. Toward nightfall, the King himself fell, struck in the eye by an arrow, according to Norman accounts, and the English gave up. William’s coolness and tenacity secured his victory in this fateful battle. He then moved quickly against possible centres of resistance to prevent a new leader from emerging. On Christmas Day, 1066, he was crowned King in Westminster Abbey. In a formal sense, the Norman Conquest of England had taken place.

King of England

William was already an experienced ruler. In Normandy, he had replaced disloyal nobles and ducal servants with his friends, limited private warfare, and recovered usurped ducal rights, defining the duties of his vassals. The Norman church flourished under his reign as he adapted its structures to English traditions. Like many contemporary rulers, he wanted the church in England to be free of corruption but also subordinate to him. Thus, he condemned simony and disapproved of clerical marriage. He would not tolerate opposition from bishops, abbots or interference from the papacy. Still, he remained on good terms with Popes Alexander II and Gregory VII—though tensions arose occasionally. Church synods were held much more frequently during his reign, and he presided over several episcopal councils. He was ably supported in this by his close adviser Lanfranc, whom he made archbishop of Canterbury, replacing Stigand; William replaced all other Anglo-Saxon bishops of England except Wulfstan of Dorchester—with Normans. He also promoted monastic reform by importing Norman monks and abbots, thus quickening the pace of monastic life in England and bringing it into line with Continental developments.

William left England early in 1067 but returned in December to deal with the unrest. The rebellions that began that year peaked in 1069 when William resorted to such violent measures that even contemporaries were shocked. To secure his hold on the country, he introduced the Norman practice of building castles, including the Tower of London. The rebellions, which were crushed by 1071, completed the ruin of the English higher aristocracy and secured its replacement by an elite of Norman lords, who introduced patterns of landholding and military service developed in Normandy. To secure England’s frontiers, he invaded Scotland in 1072 and Wales in 1081, creating special defensive “marcher” counties along the Scottish and Welsh borders.

During the last 15 years of his life, William was more often in Normandy than in England, and there were five years, possibly seven, in which he did not visit the kingdom at all. He retained most of the greatest Anglo-Norman barons with him in Normandy and confided the government of England to bishops, trusting especially his old friend Lanfranc. William returned to England only when it was necessary: in 1075 to deal with the aftermath of a rebellion by Roger, earl of Hereford, and Ralf, earl of Norfolk, which was made more dangerous by the intervention of a Danish fleet; and in 1082 to arrest and imprison his half brother Odo, who was planning to take an army to Italy, perhaps to make himself pope. In the spring of 1082, William had his son Henry knighted, and in August at Salisbury, he took oaths of loyalty from all the essential landowners in England. In 1085 he returned with a large army to meet the threat of an invasion by Canute IV (Canute the Holy) of Denmark. When this came to nothing, owing to Canute’s death in 1086, William ordered an economic and tenurial survey to be made of the kingdom, the results of which are summarized in the two volumes of the Domesday Book one of the most significant administrative accomplishments of the Middle Ages.

William The Conqueror Built Abbey of Saint Étienne Caen France and is buried there.

Death of King William I The Conqueror

William was taken to the monastery of St. Gervais just outside Rouen, France, where he lay dying for five weeks. He had the assistance of some of his bishops and doctors, and in attendance were his half-brother Robert, count of Mortain, and his younger sons, William Rufus and Henry. Robert Curthose was with the King of France. It was probably William’s intention that Robert, as was the custom, should succeed to the whole inheritance. William was tempted to make loyal Rufus his sole heir, but in the end, he compromised. Normandy and Maine went to Robert, and England went to Rufus. William died on September 9, in his 60th year. His burial in St. Stephen’s Church, which he built at Caen, was as eventful as his life. Calvinists desecrated his tomb in the 16th century, perhaps because he was a dark-skinned king, and his monument would’ve been elaborate and adorned in his likeness. It was desecrated again by revolutionaries in the 18th century.

Legacy

William left a profound mark on Normandy and England and is one of the most important figures of medieval English history. His resolve and good fortune allowed him to survive the anarchy of Normandy in his youth, and he gradually transformed the duchy into the supreme political and military power in northern France. His support for monastic reform and improved episcopal organization earned him respect from church leaders and further strengthened his hand in the duchy. As conqueror and King, William significantly shaped the history of England. His conquest of England in 1066 altered the course of English history, even though he adopted many Anglo-Saxon institutions and continued various social and economic trends that had begun before 1066. William also imposed a new aristocracy on England, French in language and culture; the English language and literature, architecture and art were transformed because of William’s conquest and great ambition for style and class. The new King and his nobles were very much involved with affairs in Normandy and France, so his focus was more on the matters of his homeland. New forms of land tenure and military service were established after the conquest, and grand castles started to be dotted around the British Isles as a symbol marking the new regime.

“For evil shall be put out, and deceit shall be quenched. As for faith, it shall flourish, corruption shall be overcome, and the truth, which hath been so long without fruit, shall be declared.”

2 Esdras 6:27-28 KJV

Disclaimer: True Race Facts have made the long overdue honest determination that the King was dark brown, aka BLACK of the Hebrew, Shemitic negro race. Based on his facial phenotype, lips and thick braided hairstyle. Authentic original coins are the most accurate determination to identify the King because he would have approved the coins before they were hammered and issued. There are many ancient FAKE coins on the market, so beware when looking at coins. The deceivers made it their mission to cover up the dark ages, so even history should now be considered pseudo-history.

Donate

Donate

I’m learning something new everyday

Very interesting, never knew William the Conquer was black….