House of Tudor, an English royal dynasty of Welsh origin, which gave five sovereigns to England: Henry VII (reigned 1485–1509); his son, Henry VIII (1509–47); followed by Henry VIII’s three children, Edward VI (1547–53), Mary I (1553–58), and Elizabeth I (1558–1603)

The origins of the Tudors can be traced to the 13th century, but the family’s dynastic fortunes were established by Owen Tudor (c. 1400–61), a Welsh adventurer who took service with Kings Henry V and Henry VI and fought on the Lancastrian side in the Wars of the Roses; he was beheaded after the Yorkist victory at Mortimer’s Cross (1461). Owen had married Henry V’s Lancastrian widow, Catherine of Valois; and their eldest son, Edmund (c. 1430–56), was created Earl of Richmond by Henry VI and married Margaret Beaufort, the Lady Margaret, who, as great-granddaughter of Edward III’s son John of Gaunt, held a distant claim to the throne, as a Lancastrian. Their only child, Henry Tudor, was born after Edmund’s death. In 1485 Henry led an invasion against the Yorkist king Richard III and defeated him at Bosworth Field. As Henry VII, he claimed the throne by just title of inheritance and by the judgment of God given in battle, and he cemented his claim by marrying Elizabeth, the daughter of Edward IV and heiress of the House of York. The Tudor rose symbolized the union by representing the red rose of the Lancastrians superimposed upon the white rose of the Yorkists.

Queen Elizabeth of York’s husband was King Henry VII, the father of Henry VIII. I could not find her original image, which is to be expected regarding anyone related to the notorious King Henry VIII. Based on her father and son, there is no way she was a caucasian woman.

Henry VII, also called (1457–85) Henry Tudor, earl of Richmond, (born January 28, 1457, Pembroke Castle, Pembrokeshire, Wales—died April 21, 1509, Richmond, Surrey, England), king of England (1485–1509), who succeeded in ending the Wars of the Roses between the houses of Lancaster and York and founded the Tudor dynasty.

Early life

Henry, son of Edmund Tudor, earl of Richmond, and Margaret Beaufort, was born nearly three months after his father’s death. His father was the son of Owen Tudor, a Welsh squire, and Catherine of France, the widow of King Henry V. His mother was the great-granddaughter of John of Gaunt, duke of Lancaster, whose children by Catherine Swynford were born before he married her. Henry IV had confirmed Richard II’s legitimation (1397) of the children of this union but had specifically excluded the Beauforts from any claim to the throne (1407). Henry Tudor’s claim to the throne was, therefore, weak and of no importance until the deaths in 1471 of Henry VI’s only son, Edward, of his own two remaining kinsmen of the Beaufort line, and of Henry VI himself, which suddenly made Henry Tudor the sole surviving male with any ancestral claim to the house of Lancaster.

As his mother was only 14 when he was born and soon married again, Henry was brought up by his uncle Jasper Tudor, earl of Pembroke. When the Lancastrian cause crashed to disaster at the Battle of Tewkesbury (May 1471), Jasper took the boy out of the country and sought refuge in the duchy of Brittany. The house of York then appeared so firmly established that Henry seemed likely to remain in exile for the rest of his life. The usurpation of Richard III (1483), however, split the Yorkist party and gave Henry his opportunity. His first chance came in 1483 when his aid was sought to rally Lancastrians in support of the rebellion of Henry Stafford, duke of Buckingham, but that revolt was defeated before Henry could land in England. To unite the opponents of Richard III, Henry had promised to marry Elizabeth of York, eldest daughter of Edward IV; and the coalition of Yorkists and Lancastrians continued, helped by French support, since Richard III talked of invading France. In 1485 Henry landed at Milford Haven in Wales and advanced toward London. Thanks largely to the desertion of his stepfather, Lord Stanley, to him, he defeated and slew Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth on August 22, 1485. Claiming the throne by just title of inheritance and by the judgment of God in battle, he was crowned on October 30 and secured parliamentary recognition of his title early in November. Having established his claim to be king in his own right, he married Elizabeth of York on January 18, 1486.

YOU DON’T DESTROY WHAT LOOKS LIKE YOU. You will notice that the nose and lips on many of my ancestor’s artefacts have either been removed, sanded down, painted or chopped off entirely. This is common practice amongst caucasians so that they can claim the identity of others, aka identity theft. It is no different from what was done to many Egyptian artefacts, with only the nose and lips removed. You don’t destroy what looks like you unless you are trying to hide something.

Yorkist plots

Henry’s throne, however, was far from secure. Many influential Yorkists had been dispossessed and disappointed by the change of regime, and there had been so many reversals of fortune within living memory that the decision of Bosworth did not appear necessarily final. Yorkist malcontents had strength in the north of England and in Ireland and had a powerful ally in Richard III’s sister Margaret, dowager duchess of Burgundy. All the powers of Europe doubted Henry’s ability to survive, and most were willing to shelter claimants against him. Hence, the king was plagued with conspiracies until nearly the end of his reign.

The first rising, that of Lord Lovell, Richard III’s chamberlain, in 1486 was ill-prepared and unimportant, but in 1487 came the much more serious revolt of Lambert Simnel. Claiming to be Edward, earl of Warwick, the son of Richard III’s elder brother, George, duke of Clarence, he had the formidable support of John de la Pole, earl of Lincoln, Richard III’s heir designate, of many Irish chieftains, and of 2,000 German mercenaries paid for by Margaret of Burgundy. The rebels were defeated (June 1487) in a hard-fought battle at Stoke (East Stoke, near Newark in Nottinghamshire), where the doubtful loyalty of some of the royal troops was reminiscent of Richard III’s difficulties at Bosworth. Henry, recognizing that Simnel had been a mere dupe, employed him in the royal kitchens.

Then in 1491 appeared a still more serious menace: Perkin Warbeck, coached by Margaret to impersonate Richard, the younger son of Edward IV. Supported at one time or another by France, by Maximilian I of Austria, regent of the Netherlands (Holy Roman emperor from 1493), by James IV of Scotland, and by powerful men in both Ireland and England, Perkin three times invaded England before he was captured at Beaulieu in Hampshire in 1497. Henry was also worried by the treason of Edmund de la Pole, earl of Suffolk, the eldest surviving son of Edward IV’s sister Elizabeth, who fled to the Netherlands (1499) and was supported by Maximilian. Doubtless the plotters were encouraged by the deaths of Henry’s sons in 1500 and 1502 and of his wife in 1503. It was not until 1506, when he imprisoned Suffolk in the Tower of London, that Henry could at last feel safe. When he died, his only surviving son, Henry VIII, succeeded him without a breath of opposition.

Foreign policy of Henry VII

In the early years of his reign, in a vain attempt to prevent the incorporation of the duchy of Brittany into France, Henry found himself drawn along with Spain and the Holy Roman emperor into a war against France. But he realized that war was a hazardous activity for one whose crown was both impoverished and insecure, and in 1492 he made peace with France on terms that brought him recognition of his dynasty and a handsome pension. Thereafter, French preoccupation with adventures in Italy made peaceful relations possible, but the support that Maximilian and James IV gave to Warbeck led to sharp quarrels with the Netherlands and Scotland. The economic importance of England for the Netherlands enabled Henry to induce Maximilian and the Netherlands to abandon the pretender in 1496 and to conclude a treaty of peace and freer trade (the Intercursus Magnus).

With Scotland the long tradition of hostility was harder to overcome, but Henry eventually succeeded in concluding in 1499 a treaty of peace, followed in 1502 by a treaty for the marriage of James IV to Henry’s daughter Margaret. James’s consent to the match may have been fostered by the arrival in England of Catherine of Aragon for her marriage with Prince Arthur in 1501. Spain had recently sprung into the first rank of European powers, so a marriage alliance with Spain enhanced the prestige of the Tudor dynasty, and the fact that in 1501 the Spanish monarchs allowed the marriage to take place is a tribute to the growing strength of the Tudor regime in the eyes of the European powers.

After Arthur’s death in 1502, Henry was in a strong position to insist on the marriage of Catherine to his surviving son, Henry (later King Henry VIII), since he had possession both of Catherine’s person and of half her dowry, and Spain needed English support against France. Indeed, in these last years of his reign, Henry had gained such confidence in his position that he indulged in some wild schemes of matrimonial diplomacy. But the caution of a lifetime kept him from involvement in war, and his foreign policy as a whole must not be judged by such late aberrations. He had used his diplomacy not only to safeguard the dynasty but to enrich his country, using every opportunity to promote English trade by making commercial treaties. He made his country so prosperous and powerful that he was able to betroth his daughter Mary to the archduke Charles (afterward Emperor Charles V), the greatest match of the age.

Government and administration

In home affairs, Henry achieved striking results largely by traditional methods. Like Edward IV, Henry saw that the crown must be able to display both splendour and power when occasion required. This necessitated wealth, which would also free the king from embarrassing dependence on Parliament and creditors. Solvency could be sought by economy in expenditure, such as avoidance of war and promotion of efficiency in administration, and by increasing the revenue. To increase his income from customs dues, Henry tried to encourage exports, protect home industries, help English shipping by the time-honoured method of a navigation act to ensure that English goods were carried in English ships, and find new markets by assisting John Cabot and his sons in their voyages of discovery. More fruitful was the vigorous assertion of royal fiscal rights, such as legal fees, fines and amercements, and feudal dues. This was largely achieved by continuing Yorkist methods in ordering most of the royal revenue to be paid into the chamber of the household, administered by able and energetic servants and supervised by the king himself, instead of into the Exchequer, hidebound by tradition. So efficient and ruthless were Henry’s financial methods that he left a fortune to his successor and a legacy of hatred for some of his financial ministers.

In restoring order after the civil wars, Henry used more traditional methods than was once thought. Like the Yorkist kings, he made use of a large council, presided over by himself, in which lawyers, clerics, and lesser gentry were active members. Sitting as the Court of Star Chamber, the council dealt with judicial matters, but less than was formerly thought. Nearly all the heavy fines levied for the illegal retaining of armed men toward the end of his reign were imposed in the Court of King’s Bench and by the justices of assize. Special arrangements were made for hearing poor men’s causes in the council and for trying to promote better order in Wales and the North by setting up special councils there, and more powers were entrusted to the justices of the peace. The king, moreover, could not destroy the institution of retainers, since he depended on them for much of his army, and society regarded them as natural adjuncts of rank. So Henry’s government was conservative, as it was in its relations with Parliament and with the church.

Character

The whole of Henry’s youth had been spent in conditions of adversity, often in danger of betrayal and death, and usually in a state of poverty. These experiences, together with the uncertainties of his reign, taught him to be secretive and wary, to subordinate his passions and affections to calculation and policy, to be always patient and vigilant. There is evidence that he was interested in scholarship, that he could be affable and gracious, and that he disliked bloodshed and severity, but all these emotions had to give way to the needs of survival. The extant portraits and descriptions suggest a tired and anxious-looking man, with small blue eyes, bad teeth, and thin white hair. His experiences and needs had also made him acquisitive, a trait that increased with age and success, and one that was opportune for both the crown and the realm.

“All lies have an expiration date, and that date is NOW. The truth will NOW reign FOREVER.”

Guinevere H Jackson

Article Citation: Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “House of Tudor“. Encyclopedia Britannica, Accessed 24 August 2022. Coin Image British Museum Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Disclaimer: True Race Facts have made the long overdue honest determination that the King was dark brown, aka BLACK of the Hebrew, Shemitic negro race. Based on his facial phenotype, lips and thick braided hairstyle. Authentic original coins are the most accurate determination to identify the King because he would have approved the coins before they were hammered and issued. There are many ancient FAKE coins on the market, so beware when looking at coins. The deceivers made it their mission to cover up the dark ages, so even history should now be considered pseudo-history.

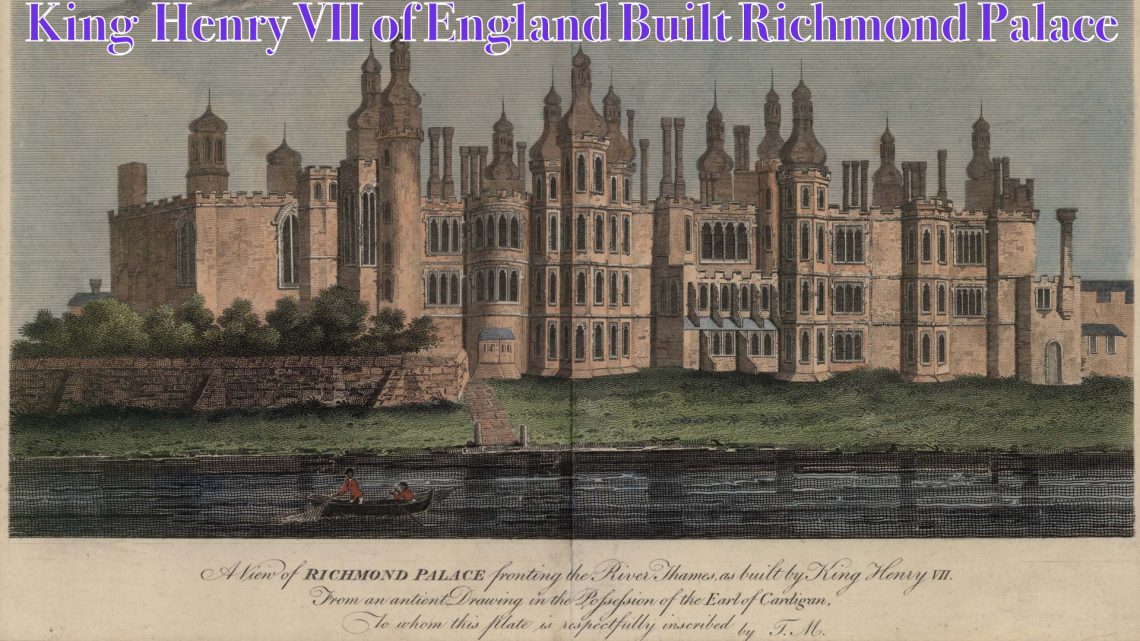

[…] was the son of Mary, Queen of Scots, and a great-great-grandson of Henry VII, King of England and Lord of Ireland, and thus a potential successor to all three thrones. He succeeded to the Scottish throne at only […]