1625c. King Charles I Of England, America Illegal Racial Execution

- Guinevere Jackson

- 6 September 2022

- 0 Comment

The beginning of so-called black people in Europe was persecuted and executed during the reign of King Charles I. I think I deserve the honour of making one of the boldest statements in history, being that I’m able to track my ancient Anglo-Saxon history to the 12th century. I’m a Jacobite survivor that’s lost it all, and I WILL NEVER ACCEPT the validity of the current British monarchy.

The British monarchy was dissolved for over ten years when Briton had no monarchy after the illegal execution of King Charles I on 30th January 1649. Ten is completion, so any monarch after Charles I, including his son King Charles II to the current newly appointed monarch King Charles III, are nothing more than puppets.

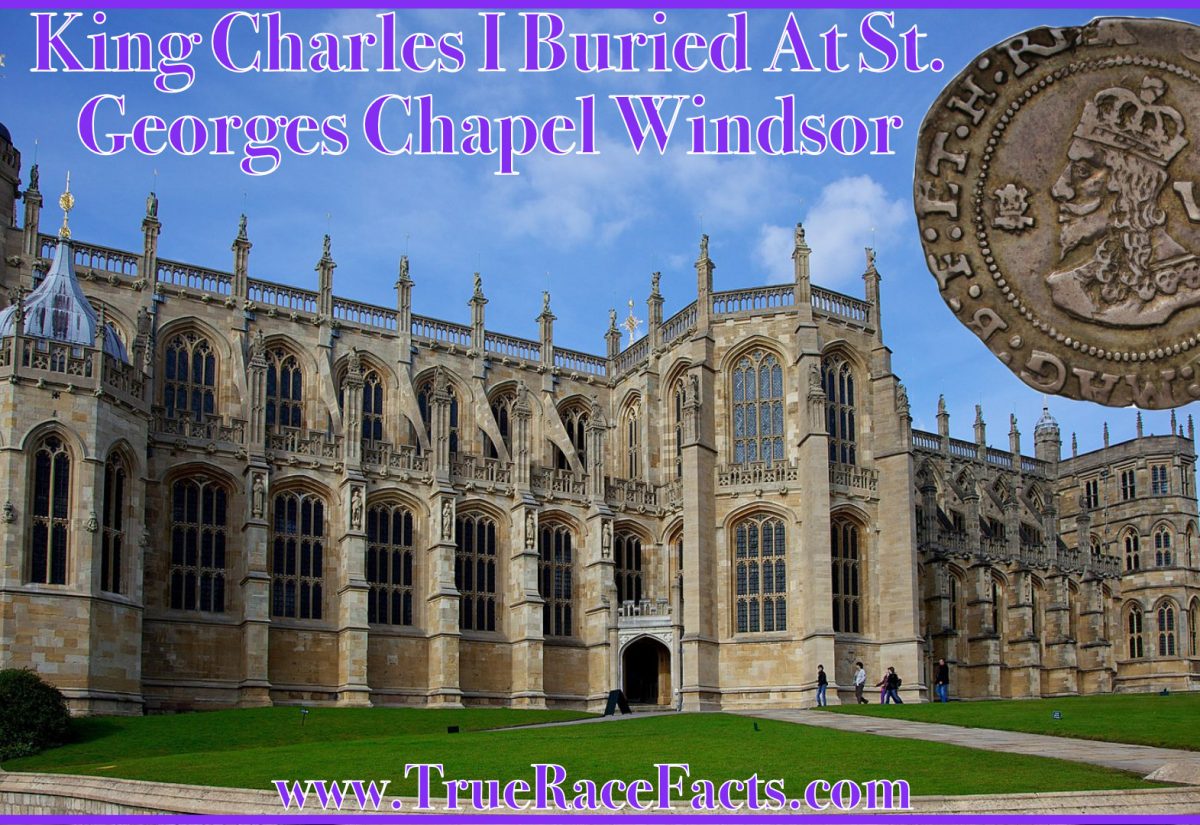

Great Seal of the Realm Charles I on a 17th-century funerary monument

King Charles I was illegally beheaded by the British House of Parliament, led by traitor Oliver Cromwell. Money and power-hungry Cromwell took a bribe from Edomite *Jewish Manasseh Ben Israel and Moses Carvajal. This bribe would lead to the overturning of the Edict of Expulsion and the start of Edomite caucasian rule. The Edict of Expulsion was a royal decree issued by King Edward I of England on 18th July 1290, expelling all Jewish people from England.

The bloodiest, longest war on record was the thirty-year Genocide in Europe, particularly in what is now called Germany, which saw a reduction of over 50% of its population. Finally, Europe was almost free of negro rulership. Only a few steps were required for the Edomites to rule Britain and the world in blood from beginning to end. Still, the Edomites needed the monarchy to be genuinely noble men and women and come away from being stinking, wild peasants. In just three months, six days after the thirty years of war, King Charles I, the last official King of England, would be put to death.

King Charles I held the key to The Divine Right Of Kings, preventing Edomites from ever becoming kings and queens. The citizens were subject to the monarchy, and in his day, not only was he the King but also the Prime Minister. So his execution was illegal unless the King agreed to his death, which he didn’t.

The Newfoundlands of America had been discovered, but the Stuarts made it clear in their American charters that the Natives of America and all citizens should be treated fairly. This meant no slavery would be allowed. His father, King James I /VI, went as far as having currency so they could trade fairly with the Native Americans, who he referred to as cousins. This means the Stuarts knew that the native Americans were of the same Jacobite bloodline. After all, they spoke Paleo Hebrew when they discovered them.

Almost immediately after the Edomite Jewish converts got back on the land, the genocide, human trafficking, and the destruction of the so-called black Israelite ruling class began. Nowhere in the Torah, Old and New Testament bible does it say that Israelites would enslave Israelites, fund and profit from their downfall. But the Bible does say, “I know thy works, and tribulation and poverty, (but thou art rich) and I know the blasphemy of them which say they are Jews, and are not, but are the synagogue of Satan.” Revelation 2:9 KJV. For the immense pain and suffering endured by Edomite Jewish converts, I refuse to classify them in the same bloodline and pedigree as my race.

If King Charles I had not been executed and been left to rule his Kingdom, the world you see today would be much better. Still, the Hebrew Edomites had a promise to take dominion of the world. The Hebrew Israelites couldn’t rule equally with their brother in this world. But a will is a will, and Esau Edom, the so-called white man, was given a constellation prize: dominion of the earth and rulership with a sword for losing his birthright and the ultimate prize, the blessing. Hollywood, the Vatican, and Churches have ignored the two main characters of the Bible, the descendants of Esau and Jacob, because the topic is highly controversial, and the current rulers do not want to admit to being the doomed Edomites. Genesis 27 KJV or NIV

I hasten to add before I’m accused of being anti-semitic, I am of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, which means I am Shemitic, aka Semitic by blood. So please, no gaslighting is necessary.

*The term Jew and Jewish should not be mixed. Jew means to be a bloodline descendant of Judah, one of the twelve sons of Jacob, referred to as Hebrew Israelites or lost sheep of the house of Israel. Jew-ISH means to pertain to or conversion but is not authentic. Edomite is the biblical term for so-called white people. I may use the term Amalekite which relates to the descendants of Amalek, the grandson of Esau. My spiritual teachers have identified Amakek as the modern-day Jewish race based on their vile behaviour throughout history against the so-called black race, aka Hebrew Israelites by blood. See the section on race, duality and the power of words. It is far more complicated than skin colour. [1]

King Charles I was born in Fife on 19 November 1600, the second son of James VI of Scotland (from 1603 also James I of England) and Anne of Denmark. He became heir to the throne on the death of his brother, Prince Henry, in 1612. He succeeded, as the second Stuart King of Great Britain, in 1625.

Controversy and disputes dogged Charles throughout his reign. They eventually led to civil wars, first with the Scots from 1637, in Ireland from 1641, and then England (1642-46 and 1648). The wars deeply divided people at the time, and historians still disagree about the real causes of the conflict, but it is clear that Charles was not a successful ruler.

Charles was reserved (he had a residual stammer), self-righteous and had a high concept of royal authority, believing in the divine right of kings. He was a good linguist and a sensitive man of refined tastes. He spent a lot on the arts, inviting the artists Van Dyck and Rubens to work in England, and buying a great collection of paintings by Raphael and Titian (this collection was later dispersed under Cromwell). Charles I also instituted the post of Master of the King’s Music, involving supervision of the King’s large band of musicians; the post survives today.

His expenditure on his court and his picture collection greatly increased the crown’s debts. Indeed, crippling lack of money was a key problem for both the early Stuart monarchs. Charles was also deeply religious. He favoured the high Anglican form of worship, with much ritual, while many of his subjects, particularly in Scotland, wanted plainer forms. Charles found himself ever more in disagreement on religious and financial matters with many leading citizens. Having broken an engagement to the Spanish infanta, he had married a Roman Catholic, Henrietta Maria of France, and this only made matters worse.

Although Charles had promised Parliament in 1624 that there would be no advantages for recusants (people refusing to attend Church of England services), were he to marry a Roman Catholic bride, the French insisted on a commitment to remove all disabilities upon Roman Catholic subjects. Charles’s lack of scruple was shown by the fact that this commitment was secretly added to the marriage treaty, despite his promise to Parliament. Charles had inherited disagreements with Parliament from his father, but his own actions, particularly engaging in ill-fated wars with France and Spain at the same time, eventually brought about a crisis in 1628-29.

Two expeditions to France failed – one of which had been led by The Duke of Buckingham, a royal favourite of both James I and Charles I, who had gained political influence and military power. Such was the general dislike of Buckingham, that he was impeached by Parliament in 1628, although he was murdered by a fanatic before he could lead the second expedition to France.

The political controversy over Buckingham demonstrated that, although the monarch’s right to choose his own Ministers was accepted as an essential part of the royal prerogative, Ministers had to be acceptable to Parliament or there would be repeated confrontations. The King’s chief opponent in Parliament until 1629 was Sir John Eliot, who was finally imprisoned in the Tower of London until his death in 1632.

Tensions between the King and Parliament centred around finances, made worse by the costs of war abroad, and by religious suspicions at home. Charles’s marriage was seen as ominous, at a time when plots against Elizabeth I and the Gunpowder Plot in James I’s reign were still fresh in the collective memory, and when the Protestant cause was going badly in the war in Europe.

In the first four years of his rule, Charles was faced with the alternative of either obtaining parliamentary funding and having his policies questioned by argumentative Parliaments who linked the issue of supply to remedying their grievances, or conducting a war without subsidies from Parliament. Charles dismissed his fourth Parliament in March 1629 and decided to make do without either its advice or the taxes which it alone could grant legally.

Although opponents later called this period ‘the Eleven Years’ Tyranny’, Charles’s decision to rule without Parliament was technically within the King’s royal prerogative, and the absence of a Parliament was less of a grievance to many people than the efforts to raise revenue by non-parliamentary means. Charles’s leading advisers, including William Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury, and the Earl of Strafford, were efficient but disliked.

For much of the 1630s, the King gained most of the income he needed from such measures as impositions, exploitation of forest laws, forced loans, wardship and, above all, ship money (extended in 1635 from ports to the whole country). These measures made him very unpopular, alienating many who were the natural supporters of the Crown. Scotland, which Charles had left at the age of 3, returning only for his Scottish coronation in 1633, proved the catalyst for rebellion. Charles’s attempt to impose a High Church liturgy and prayer book in Scotland had prompted a riot in 1637 in Edinburgh which escalated into general unrest.

Charles had to recall Parliament. However, the Short Parliament of April 1640 queried Charles’s request for funds for war against the Scots and was dissolved within weeks. The Scots occupied Newcastle and, under the treaty of Ripon, stayed in occupation of Northumberland and Durham and they were to be paid a subsidy until their grievances were redressed.

Charles was finally forced to call another Parliament in November 1640. This one, which came to be known as the Long Parliament, started with the imprisonment of Laud and Strafford (the latter was executed within six months, after a Bill of Attainder which did not allow for a defence), and the abolition of the King’s Council (Star Chamber), and moved on to declare ship money and other fines illegal.

The King agreed that Parliament could not be dissolved without its own consent, and the Triennial Act of 1641 meant that no more than three years could elapse between Parliaments. The Irish uprising of October 1641 raised tensions between the King and Parliament over the command of the Army. Parliament issued a Grand Remonstrance repeating their grievances, impeached 12 bishops and attempted to impeach The Queen.

Charles responded by entering the Commons in a failed attempt to arrest five Members of Parliament, who had fled before his arrival. Parliament reacted by passing a Militia Bill, allowing troops to be raised only under officers approved by Parliament. Finally, on 22 August 1642 at Nottingham, Charles raised the Royal Standard calling for loyal subjects to support him. Oxford was to be the King’s capital during the war. The Civil War, what Sir William Waller (a Parliamentary general and moderate) called ‘this war without an enemy’, had begun.

The Battle of Edgehill in October 1642 showed that early on the fighting was even. Broadly speaking, Charles retained the north, west and south-west of the country, and Parliament had London, East Anglia and the south-east, although there were pockets of resistance everywhere, ranging from solitary garrisons to whole cities. However, the Navy sided with Parliament (which made it difficult for continental aid to reach the Royalists), and Charles lacked the resources to hire substantial mercenary help.

Parliament had entered an armed alliance with the predominant Scottish Presbyterian group under the Solemn League and Covenant of 1643, and from 1644 onwards Parliament’s armies gained the upper hand – particularly with the improved training and discipline of the New Model Army. The Self-Denying Ordinance was passed to exclude Members of Parliament from holding army commands, thereby getting rid of vacillating or incompetent earlier Parliamentary generals. Under strong generals like Sir Thomas Fairfax and Oliver Cromwell, Parliament won victories at Marston Moor (1644) and Naseby (1645).

The capture of the King’s secret correspondence after Naseby showed the extent to which he had been seeking help from Ireland and from the Continent, which alienated many moderate supporters. In May 1646, Charles placed himself in the hands of the Scottish Army (who handed him to the English Parliament after nine months in return for arrears of payment – the Scots had failed to win Charles’s support for establishing Presbyterianism in England).

Charles did not see his action as surrender, but as an opportunity to regain lost ground by playing one group off against another; he saw the monarchy as the source of stability and told parliamentary commanders ‘you cannot be without me: you will fall to ruin if I do not sustain you’.

In Scotland and Ireland, factions were arguing, whilst in England there were signs of division in Parliament between the Presbyterians and the Independents, with alienation from the Army (in which radical doctrines such as that of the Levellers were threatening commanders’ authority).

Charles’s negotiations continued from his captivity at Carisbrooke Castle on the Isle of Wight (to which he had ‘escaped’ from Hampton Court in November 1647) and led to the Engagement with the Scots, under which the Scots would provide an army for Charles in exchange for the imposition of the Covenant on England. This led to the second Civil War of 1648, which ended with Cromwell’s victory at Preston in August.

The Army, concluding that permanent peace was impossible whilst Charles lived, decided that the King must be put on trial and executed. In December, Parliament was purged, leaving a small rump totally dependent on the Army, and the Rump Parliament established a High Court of Justice in the first week of January 1649.

On 20 January, Charles was charged with high treason ‘against the realm of England’. Charles refused to plead, saying that he did not recognise the legality of the High Court: it had been established by a Commons purged of dissent, and without the House of Lords – nor had the Commons ever acted as a judicature.

The King was sentenced to death on 27 January. Three days later, Charles was beheaded on a scaffold outside the Banqueting House in Whitehall, London *the very building that his father King James I/VI had built.

On the scaffold, he repeated his case:

The King was buried on 9 February at Windsor, rather than Westminster Abbey, to avoid public disorder. To avoid the automatic succession of Charles I’s son Charles, an Act was passed on 30 January forbidding the proclaiming of another monarch. On 7 February 1649, the office of King was formally abolished. The Civil Wars were essentially confrontations between the monarchy and Parliament over the definitions of the powers of the monarchy and Parliament’s authority.

These constitutional disagreements were made worse by religious animosities and financial disputes. Both sides claimed that they stood for the rule of law, yet civil war was by definition a matter of force.

Charles I, in his unwavering belief that he stood for constitutional and social stability, and the right of the people to enjoy the benefits of that stability, fatally weakened his position by failing to negotiate a compromise with Parliament and paid the price.

To many, Charles was seen as a martyr for his people and, to this day, wreaths of remembrance are laid by his supporters on the anniversary of his death at his statue, which faces down Whitehall to the site of his execution. After eleven years of Parliamentary rule (known as the Interregnum), Charles’s son, Charles II was proclaimed King in 1660. [2]

“He that leadeth into captivity shall go into captivity: he that killeth with the sword must be killed with the sword. Here is the patience and the faith of the saints.” Rev 13:10 KJV

“And he that stealeth a man, and selleth him, or if he be found in his hand, he shall surely be put to death.” Exodus 21:16 KJV

Verses by honorable prophets of the LORD – GMS Chicago Kingdom Come

Article Citation: [1]* Author [2]Royal.UK https://www.royal.uk/charles-i Accessed 18 Sept 2022. Images Henrietta Maria NPG-D16475 – Charles I (1625 – 49) the Scottish Rebellion, 1639, silver medal, by Thomas Simon mhcoins.co.uk – Face of King Charles I executed in 1649. Original front cover of the book Leviathan by Thomas Hobbes published in 1651. Supporters of the Stuarts were called Jacobites Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Disclaimer: True Race Facts have made the long overdue honest determination that the King was dark brown, aka BLACK of the Hebrew, Shemitic negro race. Based on his facial phenotype, lips and thick braided hairstyle. Authentic original coins are the most accurate determination to identify the King because he would have approved the coins before they were hammered and issued. There are many ancient FAKE coins on the market, so beware when looking at coins. The deceivers made it their mission to cover up the dark ages, so even history should now be considered pseudo-history.