The Gour Family of Pembridge and the Knight in Stone

- Guinevere Jackson

- 31 December 2025

- 0 Comment

14th-Century Herefordshire: The Gour Family of Pembridge and the Knight in Stone

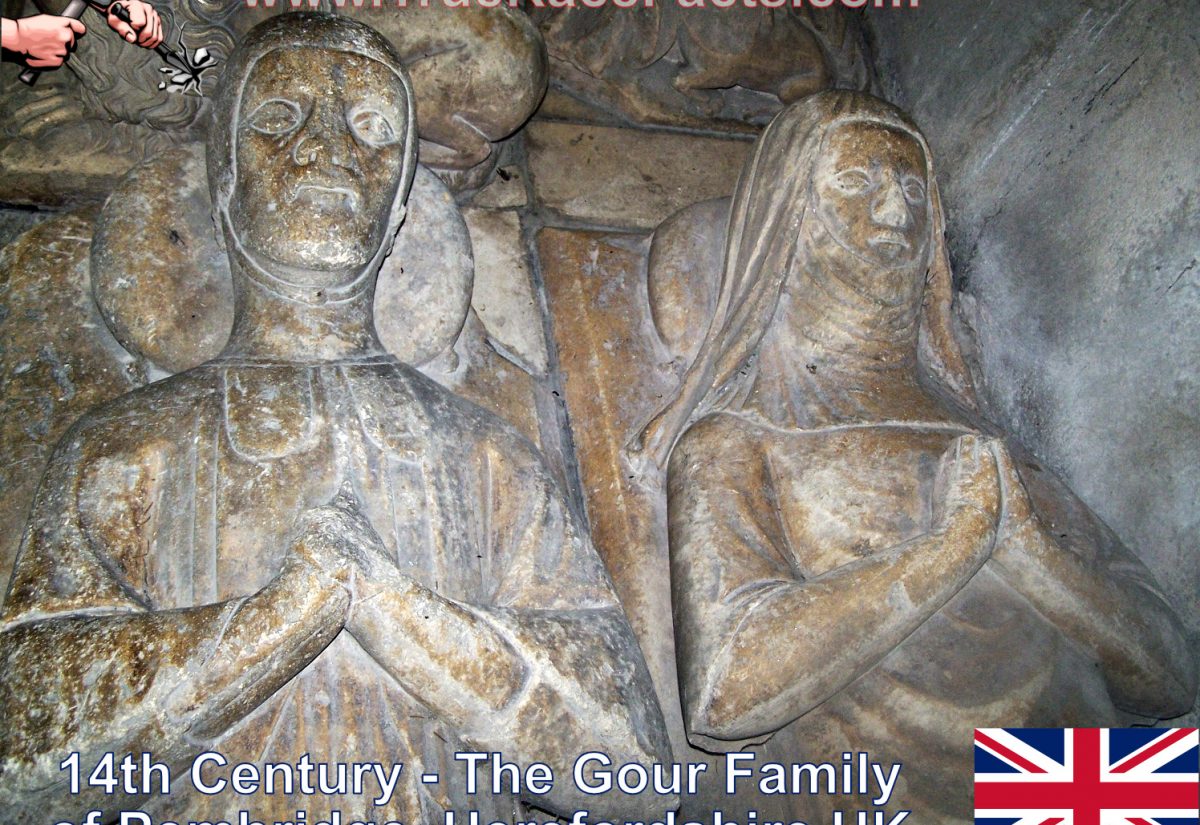

In medieval Herefordshire, the village of Pembridge stood within a landscape shaped by lineage, landholding, and knightly service. Among the families recorded in this border county during the 14th century is the Gour family, a name preserved not only in documents, but in stone.

An effigy long associated with John Gour—son of Nicholas Gour—survives as one of the most compelling visual witnesses to this family’s status. While attribution of medieval monuments often rests on tradition, location, and heraldic context rather than inscriptions alone, the identification of this effigy with John Gour has endured because it aligns with what we know of the family’s position in Pembridge at the time.

The monument itself confirms one truth beyond doubt: this was a man of rank.

Pembridge and the World of the Marches

Pembridge lay within the Welsh Marches, a region where military readiness, local authority, and noble lineage were inseparable. Families who held land here were not passive tenants; they were part of a martial society tasked with defence, governance, and continuity.

The Gour family belonged to this world.

Nicholas Gour appears in the historical record as a man of standing, and the survival of an effigy attributed to his son John reflects the family’s recognised place within the local hierarchy. Effigial burial was never granted lightly. It marked legitimacy, continuity, and remembrance within sacred space.

The Effigy Attributed to John Gour

The effigy traditionally identified as John Gour presents a fully armed knight, carved in the idiom of the 14th century. The armour, posture, and proportions place the monument squarely within the period, consistent with the lifetime attributed to John Gour.

As with so many medieval effigies, the treatment of the face is the most revealing—and the most troubling—element.

While the body and armour remain legible, the facial features appear softened and diminished in comparison to the rest of the carving. This imbalance is familiar. Across England, particularly in rural parish churches, the same phenomenon recurs: faces altered while symbols of rank are preserved.

This is not the randomness of time alone. It is selective survival.

Lineage Preserved, Identity Softened

That the effigy is linked to John Gour, son of Nicholas Gour, matters because medieval identity was familial, not individualistic. A knight represented not only himself, but his house—past and future.

The Gour effigy affirms:

inherited status,

martial authority,

and local prominence in Pembridge.

Yet, as with many monuments of England’s medieval gentry, identity is negotiated at the level of the face. The outline remains. The form persists. But detail has been reduced in a way that mirrors a wider pattern seen across 14th- and 15th-century funerary sculpture.

The past was not erased.

It was managed.

The Quiet Pattern in Parish Churches

The Pembridge effigy does not stand in isolation. Across Herefordshire and beyond, parish churches hold monuments where:

armour survives intact,

posture remains authoritative,

placement affirms nobility,

while faces appear subdued, altered, or unfinished.

This pattern invites attention—not accusation, but observation. Medieval effigies were once painted, lifelike, and intentionally expressive. When later centuries encountered faces that challenged emerging narratives about the past, the solution was rarely destruction.

It was adjustment.

What the Gour Effigy Still Tells Us

Even in its altered state, the effigy attributed to John Gour continues to speak. It speaks of a family embedded in the social and military fabric of 14th-century Herefordshire. Of a lineage anchored by Nicholas Gour and carried forward by his son. And of a medieval England more complex in appearance and identity than later centuries were willing to preserve intact.

Stone can be softened.

Details can be reduced.

But lineage leaves a deeper imprint.

In Pembridge, the Gour effigy remains—quiet, watchful, and unresolved—inviting those who stand before it to look beyond surface assumptions and listen to what medieval stone still remembers.

“When identity becomes inconvenient, monuments are broken and or adjusted. to keep the lies alive”

Guinevere Jackson

Image citation see image description

Donate

Donate