1553c. Queen Mary I England & King Philip II of Spain Holy Roman Empire

- Guinevere Jackson

- 24 August 2022

- 0 Comment

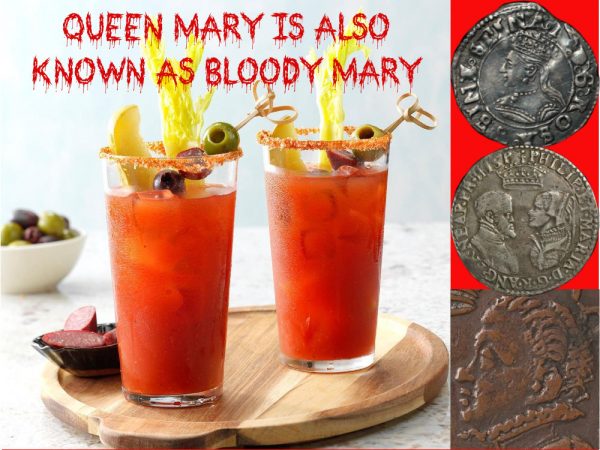

What you read about Mary I, the daughter of King Henry VIII, is most likely made up to destroy her legacy. Yet with all the talk of feminism, they fail to promote her legacy and have instead created an elaborate lie to ruin her character. Rarely will you see a street in England named after Mary. Queen Mary was the first official queen of England, not via marriage. She came to the throne when Europe was going through a renaissance, rebirth codeword for the end of so-called BLACK rulership to Edomite, caucasian rulership. I’m guessing the caucasian race was at war with the monarch for power, so in her defence, a bit of blood had to be shed hence the term Bloody Mary.

Mary I, also called Mary Tudor, byname Bloody Mary, (born February 18, 1516, Greenwich, near London, England—died November 17, 1558, London), the first queen to rule England (1553–58) in her own right. She was known as Bloody Mary for her persecution of Protestants in a vain attempt to restore Roman Catholicism in England.

Early life

The daughter of King Henry VIII and the Spanish princess Catherine of Aragon, Mary as a child was a pawn in England’s bitter rivalry with more powerful nations, being fruitlessly proposed in marriage to this or that potentate desired as an ally. A studious and bright girl, she was educated by her mother and a governess of ducal rank.

Betrothed at last to the Holy Roman emperor, her cousin Charles V (Charles I of Spain), Mary was commanded by him to come to Spain with a huge cash dowry. This demand ignored, he presently jilted her and concluded a more advantageous match. In 1525 she was named princess of Wales by her father, although the lack of official documents suggests she was never formally invested. She then held court at Ludlow Castle while new betrothal plans were made. Mary’s life was radically disrupted, however, by her father’s new marriage to Anne Boleyn.

As early as the 1520s Henry had planned to divorce Catherine in order to marry Anne, claiming that, since Catherine had been his deceased brother’s wife, her union with Henry was incestuous. The pope, however, refused to recognize Henry’s right to divorce Catherine, even after the divorce was legalized in England. In 1534 Henry broke with Rome and established the Church of England. The allegation of incest in effect made Mary illegitimate. Anne, the new queen, bore the king a daughter, Elizabeth (the future queen), forbade Mary access to her parents, stripped her of her title of princess, and forced her to act as lady-in-waiting to the infant Elizabeth. Mary never saw her mother again—though, despite great danger, they corresponded secretly. Anne’s hatred pursued Mary so relentlessly that Mary feared execution, but, having her mother’s courage and all her father’s stubbornness, she would not admit to the illegitimacy of her birth. Nor would she enter a convent when ordered to do so.

After Anne fell under Henry’s displeasure, he offered to pardon Mary if she would acknowledge him as head of the Church of England and admit the “incestuous illegality” of his marriage to her mother. She refused to do so until her cousin, the emperor Charles, persuaded her to give in, an action she was to regret deeply. Henry was now reconciled to her and gave her a household befitting her position and again made plans for her betrothal. She became godmother to Prince Edward, Henry’s son by Jane Seymour, the third queen.

Mary was now the most important European princess. Although plain, she was a popular figure, with a fine contralto singing voice and great linguistic ability. She was, however, not able to free herself of the epithet of bastard, and her movements were severely restricted. Husband after husband proposed for her failed to reach the altar. When Henry married Catherine Howard, however, Mary was granted permission to return to court, and in 1544, although still considered illegitimate, she was granted succession to the throne after Edward and any other legitimate children who might be born to Henry.

Edward VI succeeded his father in 1547 and, swayed by religious fervour and overzealous advisers, made English rather than Latin compulsory for church services. Mary, however, continued to celebrate mass in the old form in her private chapel and was once again in danger of losing her head.

Mary as queen

Upon the death of Edward in 1553, Mary fled to Norfolk, as Lady Jane Grey had seized the throne and was recognized as queen for a few days. The country, however, considered Mary the rightful ruler, and within some days she made a triumphal entry into London. A woman of 37 now, she was forceful, sincere, bluff, and hearty like her father but, in contrast to him, disliked cruel punishments and the signing of death warrants.

Insensible to the need of caution for a newly crowned queen, unable to adapt herself to novel circumstances, and lacking self-interest, Mary longed to bring her people back to the church of Rome. To achieve this end, she was determined to marry Philip II of Spain, the son of the emperor Charles V and 11 years her junior, though most of her advisers advocated her cousin Courtenay, earl of Devon, a man of royal blood.

Those English noblemen who had acquired wealth and lands when Henry VIII confiscated the Catholic monasteries had a vested interest in retaining them, and Mary’s desire to restore Roman Catholicism as the state religion made them her enemies. Parliament, also at odds with her, was offended by her discourtesy to their delegates pleading against the Spanish marriage: “My marriage is my own affair,” she retorted.

When in 1554 it became clear that she would marry Philip, a Protestant insurrection broke out under the leadership of Sir Thomas Wyatt. Alarmed by Wyatt’s rapid advance toward London, Mary made a magnificent speech rousing citizens by the thousands to fight for her. Wyatt was defeated and executed, and Mary married Philip, restored the Catholic creed, and revived the laws against heresy. For three years rebel bodies dangled from gibbets, and heretics were relentlessly executed, some 300 being burned at the stake. Thenceforward the queen, now known as Bloody Mary, was hated, her Spanish husband distrusted and slandered, and she herself blamed for the vicious slaughter. An unpopular, unsuccessful war with France, in which Spain was England’s ally, lost Calais, England’s last toehold in Europe. Still childless, sick, and grief stricken, she was further depressed by a series of false pregnancies.

Philip II, (born May 21, 1527, Valladolid, Spain—died September 13, 1598, El Escorial), king of the Spaniards (1556–98) and king of the Portuguese (as Philip I, 1580–98), champion of the Roman Catholic Counter-Reformation. During his reign the Spanish empire attained its greatest power, extent, and influence, though he failed to suppress the revolt of the Netherlands (beginning in 1566) and lost the “Invincible Armada” in the attempted invasion of England (1588).

Philip II king of Spain and Portugal

Philip II, (born May 21, 1527, Valladolid, Spain—died September 13, 1598, El Escorial), king of the Spaniards (1556–98) and king of the Portuguese (as Philip I, 1580–98), champion of the Roman Catholic Counter-Reformation. During his reign the Spanish empire attained its greatest power, extent, and influence, though he failed to suppress the revolt of the Netherlands (beginning in 1566) and lost the “Invincible Armada” in the attempted invasion of England (1588).

Early life and marriages

Philip was the son of the Holy Roman emperor Charles V and Isabella of Portugal. From time to time, the emperor wrote Philip secret memoranda, impressing on him the high duties to which God had called him and warning him against trusting any of his advisers too much. Philip, a very dutiful son, took this advice to heart. From 1543 Charles conferred on his son the regency of Spain whenever he himself was abroad. From 1548 until 1551, Philip traveled in Italy, Germany, and the Netherlands, but his great reserve and his inability to speak fluently any language except Castilian made him unpopular with the German and Flemish nobility.

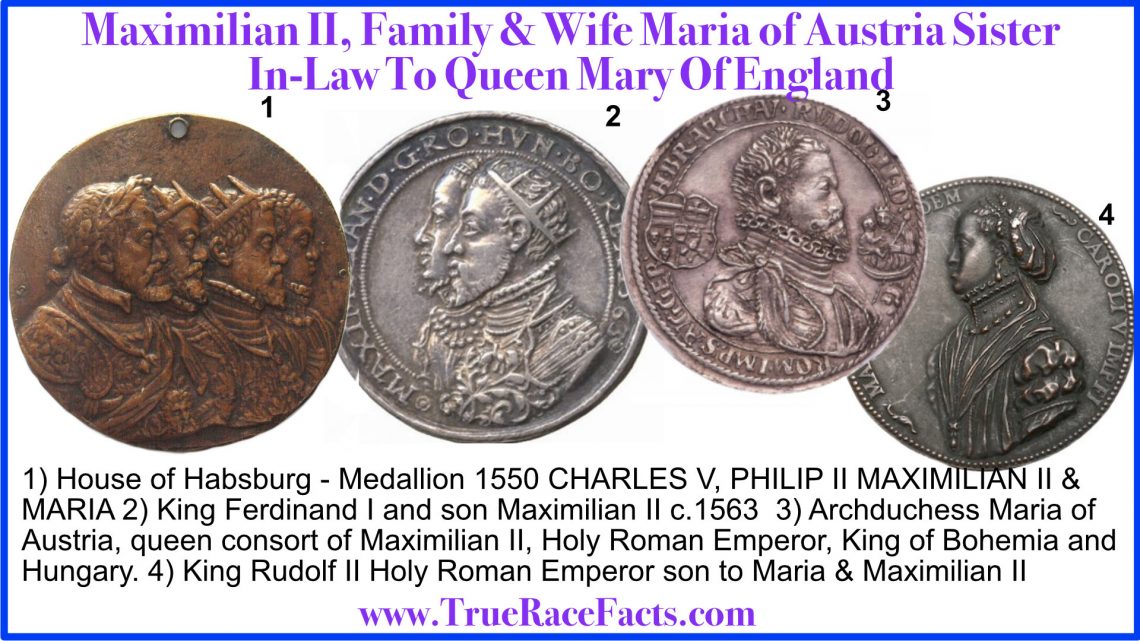

Philip contracted four marriages. The first was with his cousin Maria of Portugal in 1543. She died in 1545, giving birth to the ill-fated Don Carlos. In 1554 Philip married Mary I of England and became joint sovereign of England until Mary’s death, without issue, in 1558. Philip’s third marriage, with Elizabeth of Valois, daughter of Henry II of France, in 1559, was the result of the Peace of Cateau-Cambrésis (1559), which, for a generation, ended the open wars between Spain and France. Elizabeth bore Philip two daughters, Isabella Clara Eugenia (1566–1633) and Catherine Micaela (1567–97). Elizabeth died in 1568, and in 1570 Philip married Anna of Austria, daughter of his first cousin the emperor Maximilian II. She died in 1580. Her only surviving son became Philip III.

King of Spain

Philip had received the duchy of Milan from Charles V in 1540 and the kingdoms of Naples and Sicily in 1554 on the occasion of his marriage to Mary of England. On October 25, 1555, Charles resigned the Netherlands in Philip’s favour and on January 16, 1556, the kingdoms of Spain and the Spanish overseas empire. Shortly afterward Philip also received the Franche-Comté. The Habsburg dominions in Germany and the imperial title went to his uncle Ferdinand I. At this time Philip was in the Netherlands. After the victory over the French at Saint-Quentin (1557), the sight of the battlefield gave him a permanent distaste for war, though he did not shrink from it when he judged it necessary.

“The supreme art of war is to subdue the enemy without fighting.

Sun Tzu

Article Citation: “Maximilian II”. Encyclopedia Britannica, Accessed 2 September 2022.. Coin Image British Museum Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) Windsor Castle Image: @LuisFrancoR Flickr CC – colonialcoins.com.au, Bronze statue of King Philip II (1527-1598) By Leone Leoni and Pompeo Leoni (between 1551-1553) Prado Museum – Madrid, Spain

Disclaimer: True Race Facts have made the long overdue honest determination that the King was dark brown, aka BLACK of the Hebrew, Shemitic negro race. Based on his facial phenotype, lips and thick braided hairstyle. Authentic original coins are the most accurate determination to identify the King because he would have approved the coins before they were hammered and issued. There are many ancient FAKE coins on the market, so beware when looking at coins. The deceivers made it their mission to cover up the dark ages, so even history should now be considered pseudo-history.