12c. St. Thomas Becket or Saint Thomas of Canterbury, Thomas of London and later Thomas à Becket

- Guinevere Jackson

- 10 January 2023

- 0 Comment

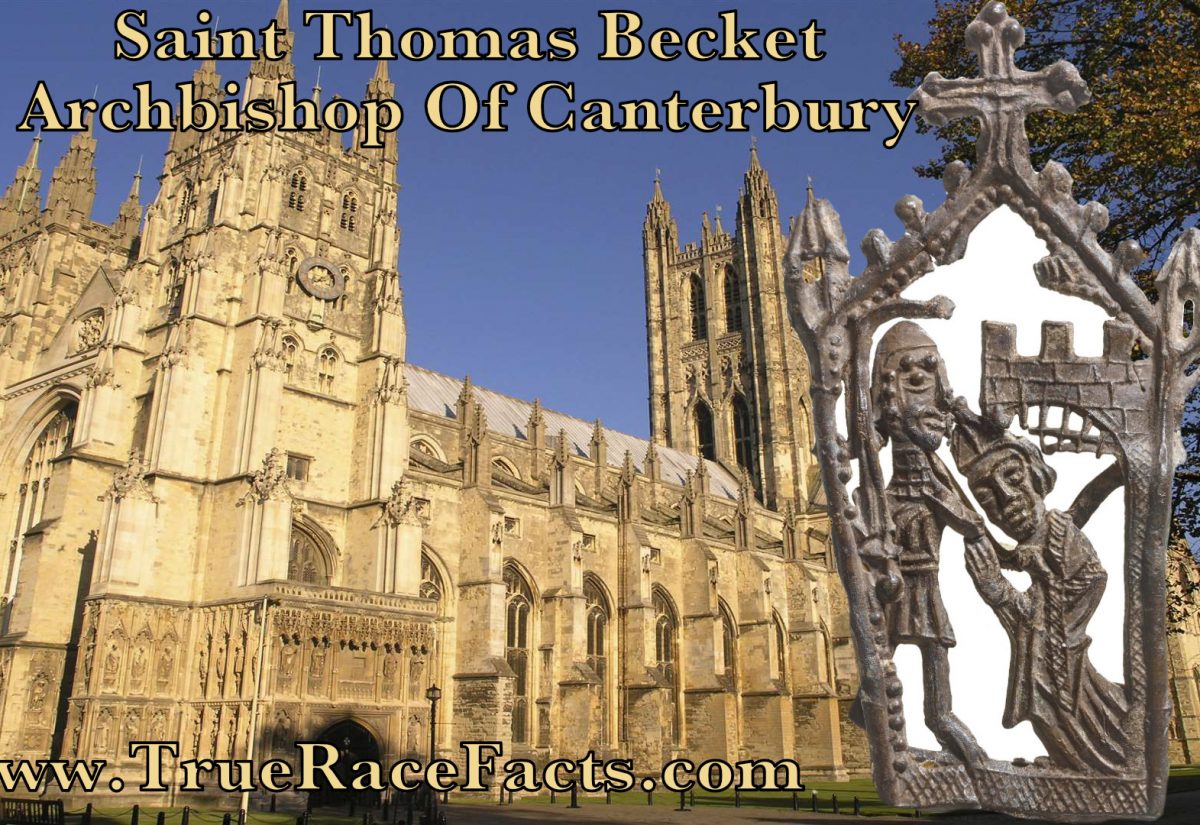

Thomas Becket was one of the most influential men in Britain. Also known as Saint Thomas of Canterbury, Thomas of London and later Thomas à Becket (21 December 1119 or 1120 – 29 December 1170), was an English nobleman who served as Lord Chancellor from 1155 to 1162 and then notably as Archbishop of Canterbury from 1162 until his murder in 1170. The Catholic Church and the Anglican Communion venerate him as a saint and martyr. He engaged in conflict with Henry II, King of England, over the rights and privileges of the Church and was murdered by followers of the king in Canterbury Cathedral. Soon after his death, he was canonised by Pope Alexander III. [1]

The murder of Thomas Becket in Canterbury Cathedral caused an international sensation, partly because of its sacrilegious nature, spilling blood in a church. Miracles were reported and attributed to Thomas soon after his death, and the broken piece of sword and a piece of his skull were kept and became famous relics. Thomas Becket was canonised in 1173 and the next year, Henry II made a pilgrimage to his tomb at Canterbury as a sign of remorse for his part in Thomas’ murder.

The only true identity of how a noble looked before the renaissance movement and the whitewashing of artefacts by Edomites is to seek out the ancient, original artefacts. Made during the time of the subject’s life or shortly after. The stained glass inside Canterbury Catherdral was thought to have been original, but it was later discovered that ALL of it had been replaced, and the original glass was never preserved.

The Cathedral has not been open about the original stained glass inside the Cathedral but we can only assume that the original featured dark skinned nobles. That is why they had them all restored or removed by Samuel Caldwell Jr., who was the person in charge of restoring Canterbury’s glass for more than fifty years. During this time, he created dozens of works and duped various church officials into believing they were genuine medieval images.

Because of the fragile nature of medieval glass, only a small amount of genuine creations have survived into the modern period. It was only in 1819 that restoration efforts were started in Canterbury. In 1897, this job was handed over to Samuel Caldwell Jr. from his father, and for the next six decades he would remove various pieces of glass from the church and take it to his workshop. Koopmans notes that Caldwell kept no drawings, photographs or written records of his work, and it seems that none of the church officials kept watch over what he was doing. This gave Samuel a lot of opportunity to create fake stained glass images as well as sell some of the real medieval works he found.

Portrait of St. Thomas Becket, reassembled from fragments by Samuel Caldwell Jr in 1919. Becket Window 1 (n. VII) in the north aisle of the Trinity Chapel, Canterbury Cathedral.

Koopmans believes that Caldwell was very proud of his craftsmanship and perhaps enjoyed fooling the various Deans and church officials at Canterbury. In some cases, he would used bits of old pieces to make the stained glass, and then explain that he had found the image in some high corner of the Cathedral which could not be seen by anyone on ground level. These images were then placed in a prominent position in the church, where they were soon marvelled at by curious crowds. Since no one in the church had anywhere near the familiarity about the glass that Caldwell had, these works were accepted as genuine.

It was not until the 1950s that some suspicions started to surface about these medieval glass works. A historian named Bernard Rackham had published a book entitled The Ancient Glass of Canterbury Cathedral, where he had proclaimed that all the images restored by Caldwell to be genuine. Two years later, when he learned that Caldwell had restored more stained glass, he wrote to a colleague at the Cathedral:

I am much interested to hear that Mr. Caldwell is producing still more panels…and a good deal puzzled. Firstly, where has all this old glass from the Cathedral been all these years? In the workshop at Blackfriars? And how did panels so nearly complete and in such good condition…come to be removed and not put back into the Cathedral? Were they taken out for repair, or to make way for modern windows by Austin and others? Whose property are they legally? Is there still a residue of old glass, and if so, where is it? I find it difficult to understand why successive Deans and Chapter should all this time have allowed not merely scraps, but whole panels of old glass to become alienated for so long from the Cathedral.

Despite these suspicions, Caldwell was never confronted with these accusations, and he died in 1963 at the age of 102. It was not until the 1970s that scholars uncovered that many of the stained glass works he restored in Canterbury Cathedral were actually forgeries. However, these works remain very popular and are still often depicted in books and on the web as genuine medieval creations. Koopmans notes that the story of Caldwell’s stained glass forgeries shows that historians need to develop “image literacy” and be able to understand how medieval objects were created. [2]

“And laid open the book of the law, wherein the heathen had sought to paint the likeness of their images.”

1 Maccabees-3:48 KJV

Citation: 1 wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Becket 10/01/23 2- From Medievalists.net November 12, 2012

Donate

Donate